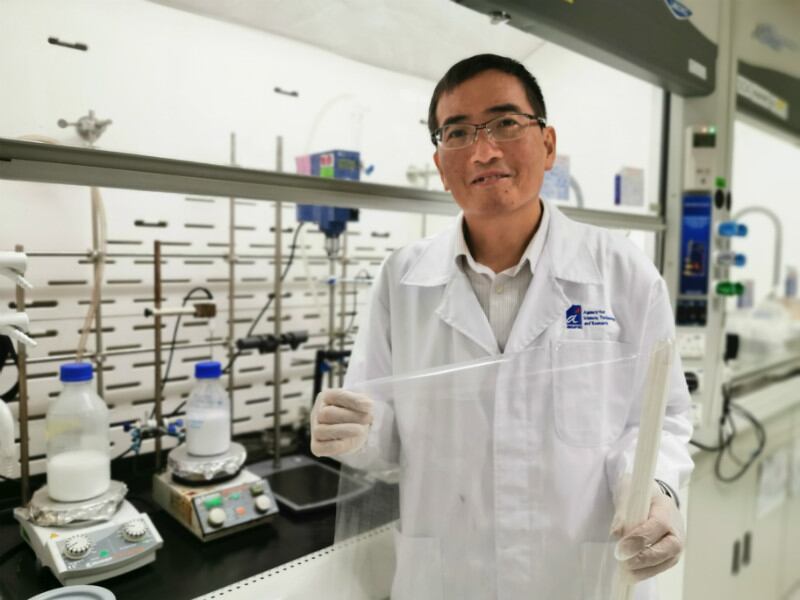

Speaking to FoodNavigator-Asia, lead researcher Dr Li Xu said the project gathered pace in in 2010 when the team observed potential high market demand for high-performance food packaging options.

“There is a huge demand for [high-performance food packaging to] reduce food waste by preserving the nutritional value of food, and keep these clean, fresh and fit for consumption, [as well as to] reduce energy consumption and reduce packaging material usage for sustainability,” he said.

He observed that the Asia Pacific packaging market is the largest worldwide, accounting for some 44% of consumption, and that plastic is currently the most common packaging material used.

The basic structure of all plastics is composed of repeating units of large molecules called polymers. Different arrangements of these polymers will result in different types of plastics being formed, e.g. chains can make plastic bottles, whereas three-dimensional arrangements are found in epoxy resin.

It is possible to insert other molecules in between the plastic polymers in order to influence the plastic’s properties, which is the concept the team used to develop their technology.

“Plastic itself is actually not very good as a barrier [to oxygen] and to moisture, [so] we used nanotechnology to insert inorganic fillers in between the polymers to improve the performance of the packaging,” said Dr Li.

“One example is silicate from a natural source, which we inserted in order to improve the oxygen barrier.”

Improving the oxygen barrier is crucial to prevent packaged premature food spoilage resulting from oxygen leaking through the packaging, which would oxidise and break down the foods.

The team has worked with a number of food and beverage companies over its oxygen barrier technology, and its technology has already been transferred to several local companies in Singapore.

In terms of sustainability, Dr Li said that this new packaging would also be able to contribute in terms of both reducing the amount of plastic used and increasing recyclability.

He added that this is in line with the 2025 sustainability target under the New Plastics Economy Global Commitment signed by over 250 organisations including Nestle, Coca-Cola, and Unilever.

“[Experts are recommending using more] mono-material packaging (plastics containing a single basic material only), as it is much easier to recycle,” he said.

“But for foods and beverages, different types and layers of materials are often needed [for different types of protection] such as preventing contact with moisture or oxygen.

“This is where our technology can come in, as we can use the nanofillers to increase the performance of each layer and [thus reduce the number of layers and material required].”

There is also potential for the technology to be applied to paper packaging moving forward, as well as for the development of decompostable packaging.

Other technology

The team has also developed an oxygen-scavenging nanofiller that can basically ‘consume’ remnant oxygen from inside food or beverage packaging to prolong product shelf-life.

“For example, in beer there is often oxygen residue left in the empty headspace (between the beer and the bottle), which can shorten the shelf-life of the product. The introduction of the oxygen-scavenging nanofiller would remove this and thus extend shelf-life,” Dr Li said.

“In the market currently, most existing oxygen-scavengers tend to emit an unpleasant odour that lingers until the bottle is opened [which is unappealing to consumers] – Our technology does not leave any sort of odour.”

The shelf-life of beer is normally capped at 18 months, as oxygen leakage into the bottle tends to take place via the cap. Dr Li claimed that coating the oxygen-scavenging material around the cap can extend this by some 20%.

“We are working with some Japanese companies on this, because the Japanese market for oxygen-scavenging materials and active packaging is huge,” said Dr Li.

Another application example he cited was tomato ketchup, where large labels or logos are generally used to cover the top layer where oxidation and the consequent darkening of the sauce is most common.

What the future holds

Dr Li also told us that the team is working with the National University of Singapore’s Food Science and Technology programme to develop a sensing material for fresh food packaging.

“This would be able to sense volatile organic compounds commonly released by spoilt fish or meat, [meaning] it would have high sensitivity as to when fresh products inside the package have been contaminated or are spoilt,” he said.

Other potential applications include for the ripening process of fruits, and the detection of temperature changes.

That said, Dr Li acknowledged that the cost of such packaging and technology will remain higher than traditional options, at least in the foreseeable future.

“We need a compromise and a balance here – it’s about food waste vs packaging waste,” he said.

“F&B companies in Asia are aware of this, and although low cost is always better, they still want to look at next generation products, and also follow global trends and government regulations, [so I believe] this still has good potential.”